Pressure Ulcers

Pressure ulcers, also referred to as pressure injuries or decubitus ulcers, are a major healthcare problem that affects patients in all healthcare settings. These wounds are the result of prolonged pressure on soft tissue, usually over bony prominences, leading to tissue damage and breakdown. This comprehensive review explores the pathophysiology, prevention, staging, treatment approaches, and advanced therapeutic options for pressure ulcers.

Pathophysiology and Development of Pressure Ulcers

How Pressure, Shear Forces, and Tissue Tolerance Contribute

Pressure ulcers result from a complex interplay between pressure, shear forces, and tissue tolerance. If external pressure exceeds capillary filling pressure, especially for a prolonged duration, local ischemia occurs, leading to tissue damage.

The Role of Ischemia, Hypoxia, and Reperfusion Injury

Initial tissue compression impedes blood flow and lymphatic drainage, causing tissue hypoxia and metabolic waste accumulation. Reperfusion injury upon pressure relief further damages tissue through inflammatory mediators and free radicals.

Key Risk Factors and Assessment

Advanced age, malnutrition, and immobility significantly increase the risk of pressure ulcers by reducing tissue tolerance and impeding natural positional adjustments. Moisture from incontinence or sweating weakens skin, while shear forces and sensory impairment eliminate protective pain responses that prompt repositioning.

Effective Strategies for Prevention

Risk Assessment: The First Line of Defense

Regular risk assessments identify patients at risk and allow for prompt preventive measures tailored to individual needs. Maintaining skin integrity through gentle cleansing, moisture management, and barrier protection prevents pressure injuries.

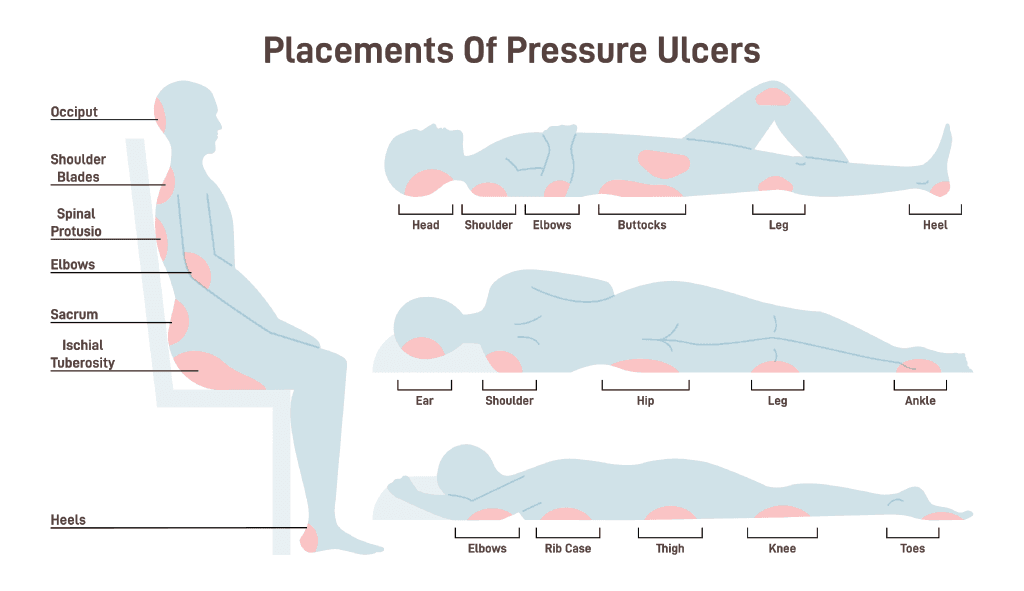

Repositioning Techniques and Support Surfaces

Individualized repositioning schedules and advanced support surfaces redistribute pressure and reduce shear forces on bony prominences.

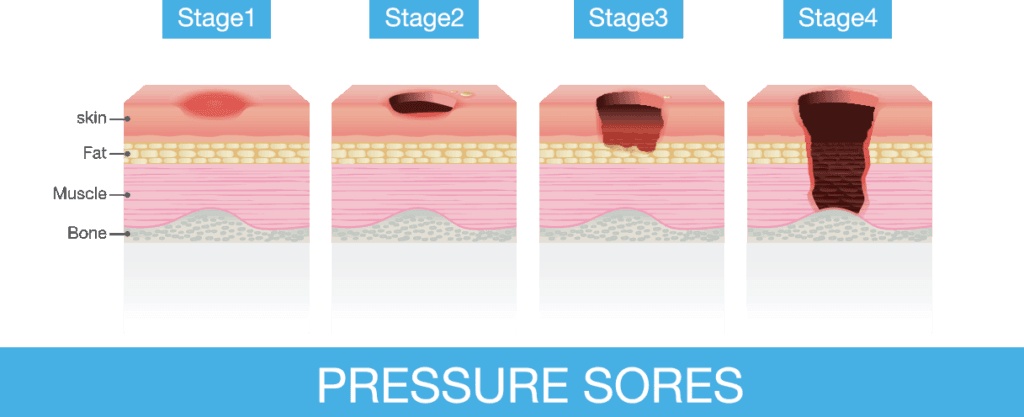

Staging and Assessment of Pressure Ulcers

Staging provides a standardized framework for treatment and monitoring wound progression.

Assessment must document wound size, depth, tunneling, necrotic tissue, and periwound skin to guide appropriate interventions.

Treatment Approaches for Pressure Ulcers

Specialized surfaces and frequent repositioning are vital for pressure relief in treatment. Debridement, infection control, and moisture balance form the cornerstone of wound bed preparation. Protein intake and balanced hydration promote tissue repair and enhance healing. Modern dressings maintain moisture, absorb exudate, and protect surrounding skin, aiding healing.

Advanced Treatment Options

Negative Pressure Wound Therapy

This therapy enhances healing by reducing exudate, promoting granulation tissue, and improving wound closure in selected cases.

Biological Dressings and Growth Factors for Healing

These products stimulate stalled wounds and support tissue regeneration when combined with proper wound care.

Amniotic Membrane Grafts in Pressure Ulcer Care

Amniotic membrane grafts have emerged as an innovative and highly effective treatment option for managing challenging pressure ulcers, particularly those that are deep and resistant to standard therapies. These grafts are derived from the amniotic membrane, a rich biological material containing growth factors, cytokines, and extracellular matrix proteins. These components work synergistically to promote angiogenesis, stimulate tissue repair, and modulate inflammation within the wound environment. By supporting these critical healing processes, amniotic grafts not only accelerate wound closure but also contribute to the development of healthier, more functional tissue in the healed area.

Amniotic grafts have shown promise in treating recalcitrant pressure ulcers by creating a biologically active wound environment that fosters healing in cases where conventional methods are insufficient. Their ability to stimulate angiogenesis is especially beneficial in ischemic wounds, as it helps improve oxygen and nutrient delivery to the affected tissue. As clinical adoption of this advanced therapy grows, amniotic membrane grafts are becoming a vital component of comprehensive pressure ulcer care, offering renewed hope for patients with difficult-to-heal wounds.

Conclusion: Comprehensive Management of Pressure Ulcers

Pressure ulcers remain a significant healthcare challenge. A combination of prevention strategies, accurate staging, tailored treatment approaches, and advanced therapies like amniotic membrane grafts provides the best outcomes. Emerging technologies will continue to improve the management of these challenging wounds.

Diabetic Ulcers

Open sores commonly on the feet, caused by poor blood flow and nerve damage from diabetes. These ulcers can lead to severe infections if untreated.

Chronic Skin Ulcers

Persistent open sores that fail to heal within 4–6 weeks, often caused by poor circulation, pressure, or underlying conditions like diabetes.

Pressure Ulcers

Skin and tissue damage caused by prolonged pressure, typically on bony areas like the hips, heels, or back, common in immobile patients.

Post-Surgical Wounds

Incisions made during surgery that require proper care to prevent infection and promote healing, varying in size and depth.

Venous Stasis Ulcers

Shallow wounds on the lower legs caused by poor blood return to the heart, often accompanied by swelling and discoloration.

Burn Wounds

Skin injuries caused by heat, chemicals, or electricity, ranging in severity from mild redness to deep tissue damage.